From The Leveller, by Ashton Starr

Thousands of people around Ottawa connected on social media to request help and offer assistance to strangers during the first spike of COVID-19 in March, 2020. They were forming COVID-19 support groups, mutual aid networks, and “caremongering” groups. Membership in these Facebook groups grew to over 4,000 within weeks, and they have remained active since then, with daily posts, comments, news, and updates.

These groups host members offering access to vehicles, distribution of prepared foods, transportation of goods seniors need, and the like. Members have also helped each other when they were unsure of how to file for the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit and Employment Insurance claims.

The BBC credits Canadians with coining the term caremongering in response to the pandemic. The term is a play on ‘scaremongering’ that aims to make kindness instead of panic contagious, according to Valentina Harper, the founder of the first caremongering group in Toronto.

From Caremongering to Mutual Aid

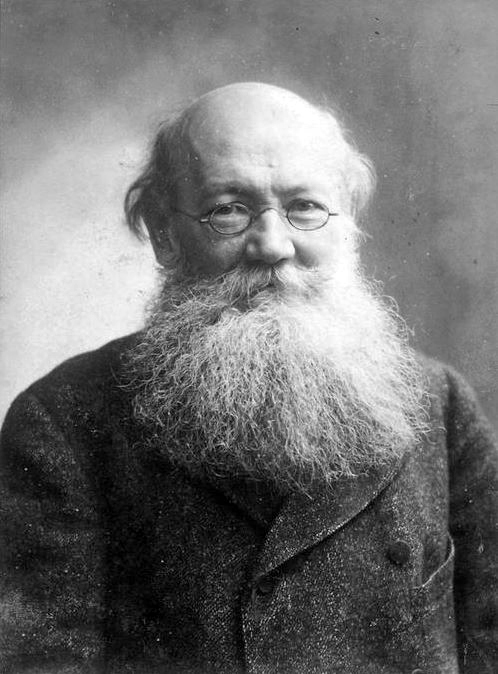

An older term to describe something similar is “mutual aid.” It is a concept with a long history in activist and anarchist circles, going back to Russian biologist and anarchist Peter Kropotkin, who argued over a century ago that cooperation was just as important to evolutionary survival as competition. Humans can and should mobilize their natural and pragmatic tendencies towards mutual aid to build a better world, according to Kropotkin.

While many might see cooperation as simple common sense, mutual aid is key in anarchist thought and practice. After all, mutual aid is a way to meet immediate human needs that is respectful and non-exploitative, as well as a revolutionary tactic to build solidarity and community power through everyday practice. The goal of such a revolution to the anarchists would be a utopia of sorts, where all relationships are organized by voluntary cooperation.

Mutual aid went on to be a key practice for many anarchists and radicals, from Catholic anarchist Dorothy Day’s houses of hospitality during the Great Depression, to the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast for children program in the ’60s and ’70s, to mutual aid disaster relief in the 2000s.

The spirit of mutual aid also continues locally as organizers create networks of neighbours and community members willing to assist each other, despite pressures imposed by city services, Ottawa police, and exploitative landlords.

Mutual Aid in Two Ottawa Neighbourhoods

In mid-March when schools and workplaces started to shut down due to the COVID-19 public health crisis, two Ottawa area activists launched mutual aid organizations to assist their neighbours. Mandy Joy started the Hintonburg/Mechanicsville Community Support Network (HMCSN) on Facebook for the neighbourhoods in the westend. Melanie Stafford started and led Overbrook Community Care for the eastern neighbourhood.

Before the pandemic, Joy was involved in anti-poverty and food-justice organizing, including bottom-lining a community kitchen at Occupy Ottawa in 2010 and volunteering with Food Not Bombs, a volunteer group that provides free meals while passing out anti-war literature. Joy also works as a contract instructor at Carleton University.

Joy created the HMCSN as a Facebook group on March 18, along with a call-forwarding phone number, a dedicated email address, and online forms for offering and requesting assistance. These resources had been used to connect people with one another based on their needs and capacities. The group quickly became a collective effort and met on Zoom with core organizers and a broader community base joining in.

“Mutual aid is about community survival,” Joy wrote to the Leveller. “It’s particularly valuable in times of crisis, but it’s based on principles that I think we can aspire to all the time – that we can work together with the people around us to build the kinds of communities that we want to live in.”

Mutual aid organizers recognize that government services often restrict, fail, and arrive late in times of need, and residents are able to fill each other’s needs more promptly and accurately.

Mutual aid differs from charity, which Joy describes as a “top-down model that moves resources from ‘haves’ to ‘have nots.’” Instead, in mutual aid, the relationships between community members are based on a level playing field, where people provide support to each other on a mutual basis.

Joy says the biggest needs have been grocery pickup and delivery for those who are immuno-compromised, higher risk, or in isolation, and who cannot go to public spaces or use public transit. Other people need financial support to purchase groceries, which many neighbours have offered to pay for directly.

Other requests include walking people’s dogs while they are in isolation, or transportation for urgent needs like medical procedures. Neighbours have readily offered these resources to one another.

Hintonburg and Mechanicsville are close, overlapping neighbourhoods, but Hintonburg has traditionally been more affluent where Mechanicsville has a very working-class history. Both are facing rapid gentrification. The resulting socioeconomic disparities can be a challenge to the mutual aid group, as there are tensions between classes and a lot of pressure on lower income residents.

In response, Joy tries to “reinforce this idea that we are all neighbours, and I think that’s productive to get people to see one another that way, but the fact is that there’s inequality here and gentrification is making this area less livable for people who have been here for a long time.”

Stafford was inspired to start her group by HMCSN’s example. She called Joy to ask how HMCSN was doing their mutual aid work, on top of contacting Nicole Marie Burton of Ad Astra Comix for use of their mutual aid illustration for Overbrook. Having a template for organizing a mutual aid group from HMCSN made for an easier start to Overbrook Community Care (OCC) in April.

The OCC started as a mutual aid group out of the safety committee of the Overbrook Community Association (OCA). The safety committee of the association had previously focused on crime prevention and police intrusion in Vanier generally. But a new crop of volunteers and organizers started to shift the focus to food security and access to proper services for the low-income neighbours living there.

Vanier has been a target of police interest for some time. In a 2011 Ottawa Citizen article, former Ottawa Police Chief Vern White said “I jokingly call it Eastboro,” a play on the affluent neighbourhood of Westboro. White speculated that properties in the neighbourhood would make good investments and mentioned that some police officers have purchased homes in the neighbourhood. This joke spoke to the police’s role in gentrification, a process which displaces poor working families from their homes and replaces them with higher wage earners — such as police and their families, in this case.

The OCA works closely with Crime Prevention Ottawa (CPO), who also work closely with the Ottawa Police Services. CPO provides funding for initiatives in the Overbrook neighbourhood, pays staff to work directly with the association and even pays for staffing of the association. The neighbourhood has also been targeted by the police’s newly formed Neighbourhood Resource Team since the fall of 2019.

Meanwhile, as a mutual aid group, OCC intentionally moved away from collaboration with the state-sanctioned security apparatus that is the police. This made sense, given the Ottawa police’s long history of violence.

“There’s not one day that I don’t interact with the police,” Stafford explains of the police presence in the neighbourhood.“And as a white woman, it is a completely different experience for me than it is for my neighbours that, on top of surviving it, have to lie about how harmful it is.”

OCC’s mutual aid also acted as a refusal of the city’s social services model that usually claims the space of community support. Stafford explains that “at the beginning, we just saw all the barriers that have always existed for access to social services were just … quite violent to access social services, and now more so.

“This was just amplifying inequities that were already in the community. Just the idea that you have to call a food bank, be interviewed, demonstrate your poverty and suffering for an audience, and have that bureaucratized is horrible and normalized.”

Stafford mentioned an example where one of her neighbours called the Ottawa’s new Human Needs Task Force, established as an emergency response to COVID-19, and did not hear back for months. The neighbour had been using the same medical mask for four months and called the task force for replacements. Stafford responded with a delivery of four cotton masks the next day.

Stafford explained that just trusting people and recognizing that the support will come from community members is a major deviation from the social services model. “Mutual aid was a natural response.” Despite mutual aid having its roots in anarchism and the writings of Kropotkin, Stafford mentioned that she only used the word “anarchist” once and that “the room was not up for it.”

“Mutual aid is a long-term, all-the-time approach to existing – call it collectivity,” she said.

As the pandemic progressed, OCC began reaching more people using a cell phone than the Facebook group. OCC members use a call forwarding plan — other groups might consider a Voice over Internet Protocol phone service — to have a phone number that redirects to their personal phone line. They have used posters to let people know about the phone line.

Some promotion of the group’s mutual aid work had come through the OCA’s quarterly community newspaper, ConneXions. Stafford and co-organizers Sarp Kizir and Danika Bisson wrote articles in the first two issues about trusting neighbours and why people need to stop calling the police.

In an interesting contrast, the Ottawa police also paid for advertisements in the same editions. Still, race-based conversations and articles in the newspaper gave space for community members to reach out to each other to discuss their experiences of racism. This included neighbours with multi-racial families who collaborated to write articles in support of Black Lives Matter.

Overbrook residents who call the OCC’s phone line have consistently connected them with fellow neighbours and OCC volunteers who delivered them food and supplies.

Stafford shared one such story, of “an elderly man who was out of food and had special dietary needs, and we kept doing a call-out like ‘Okay we need food and it’s about $80.’ Every single time, we would have someone up for paying for it and someone else up for delivering it. There’s been such an abundance in the response. This narrative that people will take advantage if you believe them or if you meet their needs has been completely debunked in our experience.”

Stafford sees that neighbours are always willing to help one another, and have been using the OCC as a channel to do so, as opposed to city services. “It’s been awesome in Overbrook. I love my community so much. To flip the script of this community being ‘deficient’ … it’s been just the opposite of that.”

Beyond the material support, one of the biggest needs during the lockdowns has been responding to loneliness and isolation. “People have been left to live alone and to be dehumanized.” Stafford identifies neighbours who not only require the grocery deliveries, but interpersonal connections, care, and love.

However, Stafford also speaks of the exhaustion volunteers and community members feel supporting one another during a public health crisis. “What I would like to see is all of our lives supported way better, so we’re not exhausting ourselves with being present and being helpful. I’m seeing that energy dissipate a lot, especially at the beginning… I don’t know how to sustain care and trust for our neighbours.”

The work that community organizers are doing to provide for their neighbours — and to build a model where that work is reciprocated — is constantly being undone by how society is directed. During the pandemic, many volunteers still need to sell their time and labour to an employer, food and supplies still cost money, and rent is still demanded by landlords. Meanwhile, the rich can safely kick back and watch their wealth grow, often without even having to lift a finger.

Both Joy and Stafford have seen activity on their groups slow down as COVID-19 numbers dropped. With cases increasing in Ottawa and winter approaching, they are expecting an increased need for mutual aid networks to become active and viable.

Joy leaves off with a personal takeaway from her experience organizing: mutual aid is a response to a short-term crisis that has potential to become a long-term structure of community-building and support. “Once you’ve got a network established,” Joy writes, “it’s an absolute waste not to continue to use it.”

Still Knocking on Doors

Another instance of mutual aid during the pandemic has involved tenant organizing. When residents in a Sandy Hill neighbourhood received eviction notices in June,the Osgoode Street Tenant Coalition (OSTC) organized a public campaign against mass “reno-evictions,” as previously reported by the Leveller.

The coalition is another local instance of renters organizing together to improve their living conditions and build tenant-power. This organizing clashes with rental agencies who hike rental fees while not following through on work orders, something both Parkdale Organize of Toronto and the Herongate Tenant Coalition in Ottawa have also fought. This systemic neglect can then be used to justify mass evictions and gentrification.

Sloane Mulligan, an organizer with OSTC, spoke to The Leveller about working with tenants during the public health crisis. “We haven’t been able to do anything online, because tenants do not have access to devices or even phones sometimes,” Mulligan said. “Some of them are older and don’t know how to use some technologies. That’s kind of been the challenge to organizing in-person safely and we haven’t had the choice.”

The lockdown has been detrimental to meeting and talking to tenants. Certain public spaces that had been used as communal spaces have been closed, increasing that isolation.

OSTC still holds meetings with tenants. “Meeting in person can be challenging, but it’s necessary. We need to make sure everyone is there and every tenant is engaged in the work… We have to get creative with that.” Mulligan continues, “We have to email, call and also leave little reminders on mailboxes. Just simply communicating and reaching people can be difficult because some people are also isolated. Everyone’s living in their own unit on their own.”

In spite of the isolation created by the crisis — or perhaps because of it — people have responded generously. “We’ve seen a lot of informal mutual aid between individuals and community members that has been very valuable,” Mulligan says. Generosity is offered and accepted more readily and without hesitations during the pandemic, they feel.

Even though meeting and talking to neighbours has been difficult for organizers, getting support or supplies has been easier.

“People have been pretty generous with donations.” Mulligan also mentioned a book sale the coalition hosted in September, as well as legal supporters offering free advice. “Non-profits have helped with printing and that is unique … I don’t think that would have happened outside of a pandemic.”

The community has rallied, knowing that many vulnerable people are facing a housing emergency because of the pandemic. “Housing is extremely important, especially in a pandemic. People who are displaced are being left very vulnerable if they have to go to overcrowded shelters. So people have been pretty generous in offering supplies and resources.”

The way community members have swung into action contrasts with the city of Ottawa, which declared a housing and homelessness emergency in January of this year but has since done little about it. The coalition has demonstrated a collective grassroots response to the amplified urgency of housing during a public health crisis. Housing organizers hope that, beyond the pandemic, their support can set an example of how community cooperation can withstand and challenge neo-liberal individualism and public policies.

Mulligan points out that “Housing is very closely tied with colonization. We’re talking about place, belonging, and ownership.” Understanding the broader context means that mutual aid work needs to follow the lead of Indigenous and Black people, people of colour, and people who are living with disabilities.

This means that Mulligan sees their work organizing with tenants as more than simply taking on a landlord. It is part of a larger process to build a culture of support, cooperation and mutual aid.